The Role of Music in Liturgical Worship: An Interview with Ryan Flanigan

AMIA Communications

What is the role of music in liturgical worship? We talked with Ryan Flanigan, Worship Director at All Saints Church Dallas, to gain insight and explore how music in the Anglican tradition enhances our corporate experiences with God.

What is the role of music in liturgical worship? We talked with Ryan Flanigan, Worship Director at All Saints Church Dallas, to gain insight and explore how music in the Anglican tradition enhances our corporate experiences with God.

What is your church background and musical training?

I was born Catholic, raised Pentecostal and educated Evangelical. Although I was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church, my earliest church memories take place in a Pentecostal church in the south suburbs of Chicago. It was a vibrant, musical church with a fantastic music minister from whom I learned a great deal about leading church music, and whose wife gave me piano lessons.

I sensed a call to vocational ministry at a young age, began leading “worship” as a high schooler and was involved in music in public school. After high school I leaned into the booming culture of praise and worship music and attended Christ for the Nations Institute in Dallas. Over the course of those two years my musical chops improved exponentially, and I wrote dozens of worship songs. The rest of my training has come through 20 years of leading church music.

How did the liturgy become a profound focus of your music and worship?

As I traveled with the Celebrant Singers at the age of 19-20, I slowly and quietly fell in love with the liturgy. Then I had the privilege of studying under Robert Webber (Founder of the Institute for Worship Studies) at Northern Seminary. Bob was the first person in my life who said it was okay to be Pentecostal, Catholic and Evangelical. This was such a relief to me, because I’d had positive experiences in all three churches.

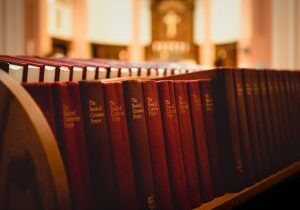

At the time I was the worship minister of a Vineyard church in Libertyville, Illinois. I immediately began putting into practice all I was learning from Bob, who had given me my very first Book of Common Prayer. The biggest thing I learned during that season was to let the music serve the liturgy. No longer did the burden of transitional flow fall on me, the song leader. The liturgy carries the worshipers, not me or anyone else.

After seminary I served for seven years at a nondenominational church in Mishawaka, Indiana. My last four years there were the most difficult and important years in my spiritual formation. My loved ones began helping me discern the call into a tradition that aligned with my worship convictions and where my musical gifts could flourish.

On April 5, 2014, I visited All Saints Dallas, the first place where I experienced three-stream worship. Never had I experienced the liturgy come alive in that way.

What role does music play in liturgical worship?

Music serves the liturgy; it does not stand as a liturgy in itself. Music aids the people in singing the praises of God. Music opens the hearts, minds and emotions of worshipers to experience the beauty of the Lord. Music is NOT a neutral vehicle for words; it is not just a cognitive exercise. A good melody can convey just as much truth as a good lyric. A song can reinforce a sermon, but a good song often moves a worshiper in ways a sermon cannot. Music can bypass the mind and speak directly to the heart. So much of our spiritual formation is noncognitive, and so we are very grateful for worship music.

How do the liturgy and the worship music enhance each other?

Liturgy frees music to be all that it can be. Without the liturgy, worship music is usually reduced to either a tool to make one feel good or a vehicle for word transmittal. Bob Webber defined worship as “proclaiming, singing and enacting the story of God.” Worship music plays a key role in the retelling of God’s story. Bob also used to say that the book of Revelation is primarily a book of worship. In it we find song after song aiding the heavenly creatures in worship.

In the AMiA approach to worship, is there a unique “Anglican” style of music, or should there be?

I wouldn’t prescribe one style to Anglicanism because the sounds that engage souls differ from culture to culture. There are sounds in the ground of every place, music that connects souls to God and to one another, the music in the bones. The question we should be asking is, “What is the sound that effortlessly engages the souls in a place?” If you’re not sure, watch the older folks and the children while you’re singing. They are the ones who are closest to the ground, living the most down-to-earth lives. If they aren’t engaging with the music, there’s a good chance you haven’t tapped into the sound in the ground.

That being said, I do think there is a particular sound arising within American Anglicanism. I call it Liturgical Folk, the music of the people. And you sort of have to experience it to understand it. The best way I can describe it is a blend of Celtic mystic, American folk and Southern gothic with historic Christian prayers, West Texas poetry and social consciousness. We have tried to capture the sound on our Liturgical Folk records, as well as take it to other churches around the country. One priest who recently hosted us on a Sunday morning put it like this:

I am sure you know this, but I want to encourage you that the Americana approach to liturgical worship is a true path for an authentic Anglican future in this country. I have spent the majority of my time in ordained ministry planting churches, and I believe that this is one very effective way forward, especially for church plants.

Tell us about the theology of lyrics.

I am a lover of words. It is essential that we sing our theology. But over the past few years I have lightened up a bit. I think there is just as much power in melody to convey truth as there is in lyric. There is certainly more potential for beauty to be shown. Of course, we’re not going to allow heresies in our lyrics, but the Western church has focused for too long on getting the words just right, and the music itself has suffered. When the music suffers, the poetry suffers. And when the poetry suffers, the words tend to be used only to convey propositional truths. We end up experiencing what C.S. Lewis experienced as a new believer: “fifth-rate poems set to sixth-rate music.” I believe the church can once again be a credible artistic witness to the world.

What is the value of singing parts of the liturgy (for example, in the Lord’s prayer)?

We are primarily liturgical creatures, and Christianity is a singing faith. Life ought to be a musical. The fact that it isn’t means we aren’t living into our full human potential. It is historically normative for the entire liturgy to be sung. I am grateful that as Anglicans we have maintained so much of our singing heritage. As my spiritual father Nelson+ Koscheski says, “We need new ways to worship God.” A new song can make us love God in new ways.