If We Only Know Scripture as a Text, We Don’t Know it at All

Dustin+ Messer

by Dustin+ Messer, All Saints Dallas

If we want to be formed in the faith, we’ll need to know Scripture. More to it, we’ll need to know Scripture as Scripture. Because if we only know Scripture as a text—a thing that we read individually, rationalistically and with modern eyes—we actually don’t know it at all.

In his book The Death of Scripture and the Rise of Biblical Studies, Michael Legaspi skillfully shows that the Enlightenment attempted to fit the Bible into the category of “text” rather than “Scripture.” He says it well:

“Academic critics did not dispense with the authority of a Bible resonant with religion; they redeployed it. Yet they did so in a distinctive form that has run both parallel and perpendicular to church appropriations of the Bible.”

In other words, the same Bible was being studied in the academy as in the church; but the academy had vastly different goals, values and presuppositions motivating its study.

Thus, Legaspi recounts the history of modern biblical interpretation as a move from “Scripture” (which is read in the church) to “text” (which is read in the academy). If one asks a biblical scholar, “What does this text mean?” one shouldn’t be surprised when he answers by simply parsing the set of words in front of him. He’s answering the question with the skill set and worldview with which he was trained.

The modern biblical scholar neglects the canonical context in which a given passage finds itself, as well as the context in which the text was meant to be read. Scripture is more than, and different than, the sum of its parts.

For example, to “know” the story of the Good Samaritan in a textual sense simply involves issues of grammar, syntax and cultural idiosyncrasies. To “know” the story in a Scriptural sense involves all those things, but also a willingness to view the needy around you as your neighbors. Said differently, to know a text exclusively involves one’s cognitive faculties. Knowing Scripture, however, might begin with the mind; but if it doesn’t end in full-bodied obedience, Scripture isn’t truly known. This, I take it, is the point of James 1:23-25. Let’s consider three ways in which Scripture is different than a text.

Firstly, a text is read rationalistically; Scripture is read theologically. A theological interpretation of Scripture is the natural consequence of recognizing the Scriptures as such. If the same Spirit who inspired Micah inspired John, then making intertextual, typological connection is not artificial, but natural, and indeed necessary! A text has one author; Scripture has two.

While the divine author is never in conflict with the human author, we should expect the divine authorial intent to be “thicker” than the human author’s intent. Said differently, the same Author who started the story (in Genesis) had the climax (in the Gospels) and the ending (in Revelation) in mind all the way through. Thus, it is only natural that we recognize the substance (the thing typified) in the shadow (the type).

Secondly, a text is read with modern eyes; Scripture demands to be read in a way congruent with the past. To be sure, Scripture always trumps any past interpretation of itself, but we would be fools to neglect the wisdom of our fathers. Thus, we can read, say, the account of Jesus’ baptism with the Trinitarian creeds in the back of our minds. We do this not with a slavish obedience to “tradition,” but with the humility and confidence that comes with being part of a Church that transcends time and space.

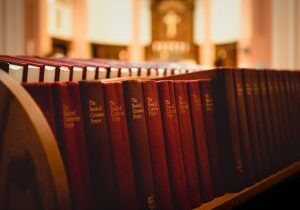

Lastly, texts are read individually; Scripture is read communally. Of course, it is perfectly appropriate to study the Scriptures on one’s own; but that is not the natural way in which to read the Scriptures. The Scriptures were written to be heard, and rehearsed, in the context of a church. Thus, if one tries to exclusively read, say, the Psalms on one’s own, the lament Psalms are either muted, or applied to fairly trivial matters.

If read in community, these Psalms are read (or sung) with the experiences of others in mind. True, every individual person in a given congregation may not be suffering, but someone in the church is. And, when these Psalms are read communally, the suffering person’s burdens are borne by the whole community.

When Scripture is read in community, the interpretation of each reader is accountable not only to the ancient Church, but to the local church. The perspectives of various genders, ages, cultures and ethnicities work as a safeguard for any one person’s interpretation. Reading Scripture is a communal act in which each individual reader is brought into an accountable relationship with every other reader.

In conclusion, what is needed in our day is a pilgrimage away from the academy and to the Church. What is needed is a call to read the Bible in a way that’s ancient, communal and theological. Indeed, one can’t be formed in the faith by a mere text. For that, we need Scripture.

The Rev. Dr. Dustin Messer serves as a priest at All Saints Dallas in downtown Dallas, TX. Additionally, Dustin is a regular contributor to The Gospel Coalition and teaches in the department of religious and theological studies at The King's College in New York, NY. A graduate of Boyce College and Covenant Theological Seminary, Dustin earned a doctorate in ethics at La Salle University and went on to complete a fellowship at the Center for the Study of Statesmanship at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. Along with his work in local parish ministry, Dustin has served in positions of leadership for a number renewal organizations within the broader Anglican church, including the Global Anglican Future Conference (GAFCON) and the Evangelical Fellowship in the Anglican Communion (EFAC). Dustin is married to his college sweetheart, Whitney, and they have one daughter, Pennilyn Grace.

Category: Scripture, Spiritual Growth

Tags: Text