Between Two Traditions: Anglican Views on Holy Communion

Gavin+ Pate

Some friends of ours had a chance to visit Rome last year. While there, they attended a Eucharistic Adoration service. In this service, the host (the large piece of bread used in Holy Communion) was placed in a glass box. This glass box was placed in the center of the altar and praises were sung and said to the bread. This was the height of the Roman-Catholic understanding of Holy Communion.

Some friends of ours had a chance to visit Rome last year. While there, they attended a Eucharistic Adoration service. In this service, the host (the large piece of bread used in Holy Communion) was placed in a glass box. This glass box was placed in the center of the altar and praises were sung and said to the bread. This was the height of the Roman-Catholic understanding of Holy Communion.

I grew up in a tradition where Communion was served every Sunday. On a recent vacation, I visited one of these churches. Communion was penitential. The elements were bread and grape juice, nothing more, nothing less. Not a person present would have stood to say otherwise. This expression of The Lord’s Supper was a textbook product of the Radical Reformation.

In the Anglican Church, we stand firmly between those two traditions. While not expressly articulating the line of the Roman-Catholic church, we still believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. While we do not make any demands on parishioners to account for their mental state when receiving the bread and wine, we make clear in our liturgy that the bread and wine they receive is more than what they consumed at their last steak dinner.

Therein lies the glory of the Anglican position on Holy Communion. We are communing together, having a relationship with one another as we feast on the Lamb of God. This time and this sacrament are set apart, special, wholly other. This high view of Holy Communion is part of what makes us historically catholic. We did not sit out the enlightenment; we did resist many of the reformations that later Protestants did not.

There are two peaks in our worship: the Word preached and Holy Communion. In contrast, the peak of a Roman-Catholic worship service is Holy Communion, whereas in other Protestant spaces, the Word preached is superior to all else.

In the Anglican Communion, we have two sacraments (ways of receiving grace from God). These are baptism and Holy Communion. By contrast, the Roman-Catholic church has seven sacraments. Many Protestant churches never use the term “sacrament,” as it thought to be confusing.

The basis for Holy Communion comes from the communal Passover meal shared among Jesus and his disciples just before the His arrest. We find the account of this meal in all four of the Holy Gospels.

In the Anglican Communion, Holy Communion is both an encouragement to the journeying Christian and a celebration of the communion each Christian has with the Trinitarian God we worship, as well as with one another.

In the early church, most Christians accepted Holy Communion as a communal meal of grace for the church. Once the Protestant Reformation began to gather steam, the debates over the real presence of Jesus in the elements began to emerge. People hold many views on Holy Communion, but essentially, all views can be categorized into two “buckets.”

The first group would be called “positive speculation.” This group assumes that the words of Christ were meant to be taken at face value and believe that there is more in the bread and wine than merely bread and wine. Included in this group is the belief that the bread and wine are transformed into the actual body and blood of our risen Lord, Jesus Christ.

The second group would be called “negative speculation.” This group assumes that while, yes, Christ said that this (bread) was his body, he never meant for anyone to take that literally. Instead, this group applies rational thought to Holy Communion and primarily observes the time as one of remembering the sacrifice of Jesus Christ.

The Anglican Church encompasses a wide variance of views. Anglicanism is not meant to be a denomination, as such, but a catholic (universal) alternative to the Roman church. As a result, you won’t find one required belief about what happens to the bread and wine in Holy Communion. Some Anglo-Catholics believe in a literal body and blood in the elements. More evangelical Anglicans recall the death and sacrifice of Jesus, denying that anything materially changes in the bread and wine themselves.

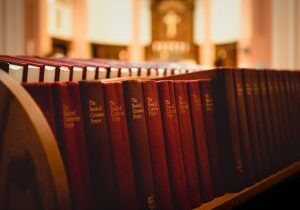

In the 1979 Prayer Book (the most common version in the United States), most of the liturgy points to a high view of the Eucharist. The view is not quite as high as the Roman-Catholic church, but much more than a memorial where common bread and wine are consumed.

In Holy Communion we are connected historically and globally, across time and space in the great expanse that is the church catholic. Holy Communion is a living preview of the wedding feast all faithful Christians will experience in Heaven. It is a meal of sustaining grace, embodying the prayer of Jesus, that Our Father would “give us this day our daily bread.”

Gavin+ Pate has been a part of various church plants. He also spent three years working for a regional church planting network.

Category: Sacraments, Spiritual Growth

Tags: Holy Communion, Roman Catholic, Text