How I Found Myself in The Confession

Lucas Damoff

Celebrant: Let us confess our sins against God and our neighbor.

Silence may be kept.

Celebrant and people:

Most merciful God,

I confess that I have sinned against you

in thought, word, and deed,

by what I have done,

and by what I have left undone.

I have not loved you with my whole heart;

I have not loved my neighbors as myself.

I am truly sorry and I humbly repent.

For the sake of your Son Jesus Christ,

have mercy on me and forgive me;

that I may delight in your will,

and walk in your ways,

to the glory of your Name. Amen.

The Bishop, when present, or the Priest, stands and says

Almighty God have mercy on you, forgive you all your sins through our Lord Jesus Christ, strengthen you in all goodness, and by the power of the Holy Spirit keep you in eternal life. Amen.

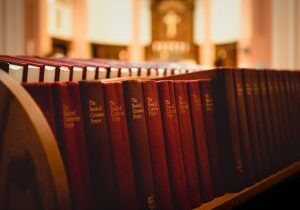

Growing up in an Episcopal school, we did chapel twice a week. Among all the elements of the liturgy that we were exposed to, the Confession of Sin had the most profound effect on me as I grew into adulthood. Even after leaving for public high school and then college, seven years of repeating this prayer twice a week had left it indelibly written in my memory. As I left a more liturgical tradition for a time, I found many of the prayers and Psalms we recited would come to mind on various occasions. But (and this perhaps reveals rather more about myself than I should) the Confession was the one that came up the most often and was the one that I was most grateful for.

There is something comprehensive about the Confession: sins of commission (“what I have done”) and omission (“what I have left undone”); sins of thought, speech, and action; and, that most tricky of sinful dispositions, loving God and neighbor more weakly than I love myself. All of these find expression here.

Even before my return to the Anglican tradition I found myself coming back to this prayer time and again. It served as a grid through which to view my various sins as I increasingly have become aware of them, as well as my sinfulness. Furthermore it served as a useful vessel for taking all these things to God. On those days I found myself to be spiritually out of sorts, where I realized that my life didn’t look like it ought, but at the same time I couldn’t point to the issue, I could always begin: “Most merciful God, I confess…”. The Confession serves at the same time as a plea for forgiveness as well as an invitation to the Holy Spirit to work conviction. In effect, it opens the doors of my heart to the Holy Spirit and says, “Come in and show me what has gone wrong and where I have offended the grace I have received. Is it my thinking that is amiss? Have I somehow neglected my proper duties? Or is it that I simply love too weakly?”

But also in those times where I have sinned in a more high-handed way. Where I have sinned and know the sin well, where I have consciously chosen to do something I know I ought not have done—here too the Confession is useful. It begins by asking for mercy, and it ends by pointing me to the cross. I am reminded that I don’t get to demand forgiveness as my right, I ask for it for Christ’s sake. Forgiveness is Christ’s birthright, he is the one who lived a perfect life, died a perfect death, and was raised back to glorified life. He has paid the debt that I owe, so any appeal I can make must be made in respect to His work.

And suddenly my sin is put in the context of the cross. I am made to remember what this mercy cost Jesus and in so-doing I am made to see my sin as abhorrent. And this illustrates the great problem of sin, and the crucial importance of regular confession and repentance. Sin isn’t such a big deal merely because it makes God upset, as if he arbitrarily set up rules and then gets petulant when we don’t play by the rules. Sin, all sin, is relational. All sin is an affront to God’s love for His creation. Thus, in Psalm 51, David can say to the Lord, after committing adultery with Bathsheba and murdering her husband Uriah, “Against you, you only, have I sinned and done what is evil.” As God’s creatures he knows us better than we know ourselves. He is closer to us than we are to ourselves. He loves us more than we love ourselves. God doesn’t hate sin because sin is bad for Him. God had no intrinsic need to create; He was (and is and always will be) perfectly satisfied in the mutual giving and receiving of love that happens within the life of the Trinity. It is out of this love that He created the universe, so that other creatures might share in that love. Sin grieves God because it is His creatures willfully turning away from that perfect love, and toward their own destruction.

Yet this is not the final word, I am not left simply in sorrow over my sin, even if it is godly and repentant grief. Instead I find the renewed offer of a grace-filled life. God’s merciful forgiveness doesn’t just return me to some neutral relationship where I can try again and this time maybe do better. Instead I am restored to a positive relationship: I am offered not just a do-0ver but delight. I am returned to the place where I am able to glorify God and enjoy Him in perpetuity.

Lucas Damoff wrote this while working with communications at All Saints Dallas.

Category: Faith Formation, Sacraments, Spiritual Growth

Tags: Text, The Confession