Being a Missionary in a Missionary Society

Dustin Freeman

In 2002, after graduating from college in Arkansas, I moved to a rural part of Mali, West Africa to work as a church planter. While living there, I kept up a steady correspondence with a friend from college who eventually moved to Bangladesh, also serving as a missionary. After a few years of letter writing, this friend became my girlfriend, and we each made our way back to the U.S. to pursue our relationship and return to school. We had both learned the hard way that we needed more and deeper skills to serve well in the kinds of environments we had been living in; so we studied, got married and went looking for a new home church, always assuming that our ultimate trajectory was a career together in international missions.

In 2002, after graduating from college in Arkansas, I moved to a rural part of Mali, West Africa to work as a church planter. While living there, I kept up a steady correspondence with a friend from college who eventually moved to Bangladesh, also serving as a missionary. After a few years of letter writing, this friend became my girlfriend, and we each made our way back to the U.S. to pursue our relationship and return to school. We had both learned the hard way that we needed more and deeper skills to serve well in the kinds of environments we had been living in; so we studied, got married and went looking for a new home church, always assuming that our ultimate trajectory was a career together in international missions.

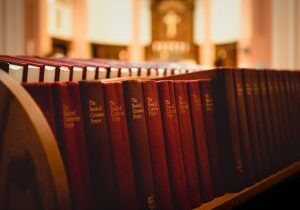

In 2008 we began regularly attending St. Andrew’s Church in Little Rock, Arkansas. I didn’t really know anything about Anglicanism when we visited the first time, but I was immediately intrigued by its three-stream approach to worship and its relationship to other Christians around the world. Hearing that St. Andrew’s was somehow under the leadership of bishops from Africa was especially interesting to me.

Soon, my wife and I started exploring what it might mean to be Anglican missionaries. We were very eager to see how being part of a global communion with international leadership might make us better cross-culture workers. We knew firsthand how easy it is to unintentionally confuse aspects of our home culture with the gospel, creating unnecessary stumbling blocks for conversion and discipleship; and meaningful partnership with Christians from other cultures seemed like the best possible way to locate those kinds of blind spots.

It was a great surprise then (while attending a class on international missions no less) that God called my wife and me to “be missionaries here” in Little Rock. This call came clearly, but without specifics. We understood that we were to live with the same kind of intentionality and focus that we had while living overseas. We knew that we were meant to share the love of Christ and make disciples and that this was our primary daily task. We just weren’t sure where to start. Thus began a new journey that eventually led to my ordination and a decade of pastoral ministry here at St. Andrew’s.

On the surface, the call to cross-cultural missions that I initially received and the call to pastoral ministry in my own home state sound like they are at odds, but I have come to see that they are very much in harmony. When I lived in Mali, I began learning to pay attention to the world around me in a new way, to notice culture: the hidden rules, stories and assumptions that are invisible to all who hold them but essentially run their world. Coming back home, I was a little more able to see my own culture, things I simply would not have noticed until I had lived somewhere with a different set of rules, stories and assumptions.

Today, living in Little Rock, Arkansas, it is clear that the community that I serve, and communities like it all across the U.S., are going through an era of major cultural change. As the modern era gives way to post-modernity and Christendom becomes post-Christendom, leaders need missionary skills: the ability to discern culture, to understand how it is shaping our faith and practice, in order to respond in ways that are faithful to Jesus. Of course, this is easy to say and much harder to do. How can you know what you don’t know? How can you see the profound influence of your own culture on yourself, when everyone around you has been shaped in the same powerful but invisible ways? We all need help to do this, and thanks be to God, he has provided it.

The New Testament tells the story of a church that was always meant to be comprehensively diverse, ultimately including people from every “nation, tribe, people, and language” (Revelation 7:9) and yet also profoundly unified (John 17:21-24). As Anglicans, this vision has a tangible expression for us, through the global communion that we are a part of and the common worship that we participate in.

The Church, in all of its vast, diverse oneness, is one of God’s greatest gifts to every individual Christian and has never been an optional aspect of our faith. This is true theologically, as the Eucharist makes it clear that being one with Christ also means being united to each other. But this unity isn’t just academic or something that will only matter on the other side of the resurrection. It is the unique gift that gives us the opportunity to see beyond our own cultural blind spots here and now.

Only by having real relationships of give and take with other people who belong to Jesus from other cultures will we gain the perspective to see ourselves clearly. It is hard work negotiating cultural differences with believers from significantly different cultural backgrounds, and we may wonder if it is worth it at times; but it is the necessary preparation for faithful engagement with our own cultural challenges. For us in the AMiA, the partnerships that we have through our mission partner bishops are one of our clearest and best opportunities to take advantage of this deeply necessary gift.

This past summer, my wife and I traveled to Tanzania to celebrate Bishop Sospeter’s son’s wedding and to spend some quality time with the churches of the diocese of Kibondo. The hospitality we experienced there was wonderful, and the worship we were able to participate in was a great encouragement. Even so, some might wonder if the significant expense, in terms of both time and money, of making a trip like this is worth it. I write all of this today to try and communicate that it is, indeed, very worth it. While the impact of a trip like this is very hard to quantify, it is not a single point of contact, but the ongoing, and consistent investment in real, meaningful relationships with co-laborers in Christ’s fields from around the world that gradually give us that distinctive unity-in-diversity shape that was always meant to be an essential mark of the Church. How can this happen if we never go?

The AMiA’s call has ever been a missionary call, to reach the unchurched in the U.S. We are then all missionaries in a missionary society. As America’s culture changes rapidly, doing this well will require missionary skills. I know of no better way to pursue this equipping than to invest significantly in the international relationships we already have. I highly recommend visiting our bishops to all of you. If you go, you will be blessed, and the AMiA will grow a little deeper into the shape and purpose to which it is called.

Dustin+ Freeman has served as associate pastor at St. Andrew's for the past decade, after previously serving as a missionary church planter in Mali, West Africa. He holds a Master of Public Service from the University of Arkansas' Clinton School and a Master of Theology and Mission from Northern Seminary. He and his wife, Beth, have five sons between the ages of 13 and 2, who make the beauty and urgency of Jesus' command to make disciples very real every day.

Category: Anglicanism, Evangelism and Outreach, Personal Story