The Via Media and the Muddled Middle

Chris+ Myers

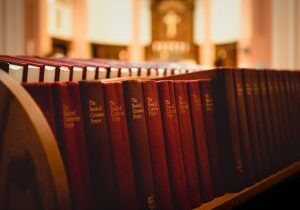

For me, the via media is a way of saying that Anglicans are attempting to practice a Reformed Catholicism. We can think of this in geographic terms, where Canterbury, Anglicanism, occupies the territory between Geneva and Rome, between Calvinism and Catholicism where Canterbury is not a city in isolation, but rather a center of commerce, trade and interchange with the other two cities.

For me, the via media is a way of saying that Anglicans are attempting to practice a Reformed Catholicism. We can think of this in geographic terms, where Canterbury, Anglicanism, occupies the territory between Geneva and Rome, between Calvinism and Catholicism where Canterbury is not a city in isolation, but rather a center of commerce, trade and interchange with the other two cities.

In Anglican thought via media was first used in a retrospective sense to describe an impulse Newman, Keble, and others in the Oxford Movement perceived in Anglican theology, particularly in the work of Richard Hooker. They saw in Hooker an articulation of a mediated position that was neither Puritan nor Papist. What Hooker was describing was a true third thing, a Reformation movement that took seriously the critiques of the Continental Reformers but at the same time was mindful not to neglect the riches of the truly catholic past, a critique that was able, in our perspective, to see the best in the other two approaches and bring them together into something simultaneously new and old.

Even so, there are a couple of important things to remember about Hooker’s Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, his magisterial articulation of Anglican polity. For one, he never uses the term via media. For another, Hooker was in a particular environment where he found himself needing to articulate a position on church polity in contrast to the Puritans and the Papists. He was doing many things at once, but primarily he was making an argument for polity, so Hooker’s intention was never for his approach to become a de facto approach on any given theological issue. This is important to remember because as things developed there has been a temptation to do just that.

Daniel Saunders in a blog post for The Common Vision cuts to the heart of the issue, and I would commend the rest of the post I’m about to quote to you and the whole Common Saints series of posts, especially the post on Richard Hooker, which provides good background for where the idea of the via media comes from, if not the term itself. Saunders says, “Neither Catholic nor Calvinist (or maybe both/and): this is precisely the via media, the intermediate ground, as it were, that has always been the defining feature, the blessing and the curse, of the Anglican tradition.

The vagueness of this formulation has allowed for the incredible diversity of theological expression found within Anglicanism, which spans the gap between Rome and Geneva—the high-church worship of the Mass and the low-church worship of the evangelical praise band; the sacramentalism of the Catholics and the iconoclasm of the Reformers; the creeds of the early church and the postmodern blather of the twentieth-century liberal church; the Arminianism of John Wesley and yes, even the tempered Calvinism of J. I. Packer. But the broadness of the via media comes with a certain lack of focus. After the spectrum is surveyed, the question remains: what is distinctive about Anglican doctrine?”

What Saunders is saying, and I agree, is that as a way of approaching Christianity and “doing” theology, the via media is a sword that cuts both ways. On the one hand, the via media as a sensibility leads to something that many describe as the Anglican temperament characterized by a reasonable even-handedness that is comfortable navigating tensions. On the other hand, the via media can become a nervous tick, an unhelpful default mode of theology where the goal in any controversy is to find the mediated position, the so-called middle way. But what if the two points being navigated actually distort the question instead of accurately framing it?

From a practical standpoint, what this means is that moderation is not necessarily a good in and of itself and is not necessarily something that should be sought for its own sake or above all else. For many the revision of prayer books brings these exact issues to the surface where the end product can feel to some more like muddle than the middle.

We can take this even further though. When we think about this in terms of the Christian life and what it means for us to love God and love others, moderation as an end itself is even more dangerous. Moderate love is not very loving at all. What we want from love is quite the opposite than moderation. One of my favorite songs from this past year, “Dark Side of the Moon” by Chris Staples, gets to the heart of this. In the chorus he sings to his child, “I want to love you. I want to pass it on. I want to give and give until its all gone. I want to know you while we’ve got the time cause that’s all we’ve got to leave behind.”

This is love at its best, an immoderate pouring out of all that we are and all that we have for the sake of another. After all, the center of our faith is the example par excellence of immoderate love–the willing sacrificial death of the Son of God. As attempt to walk the middle way, might our love be immoderate in exactly this way.

Chris Myers serves as the Curate of St. Bartholomew’s Anglican. He graduated from Redeemer Seminary with an M.Div. in 2013 and was ordained as a priest in the Anglican Mission in May of 2014. He recently finished his PhD in Theology from Durham University (UK), writing on the theology of Hans Urs von Balthasar. He and his wife Morgan have two delightful daughters, Eleanor and Rowan.

Category: Faith Formation