The Hope of the Church in 2024 Politics

Guest

By Abby M. McCloskey, All Saints Dallas

By Abby M. McCloskey, All Saints Dallas

There are plenty of reasons to be discouraged about American politics in 2024. Lest you need reminders, here are a few: Political polarization is at levels not seen since the Civil War. According to Pew Research, 72% of Republicans regard Democrats as more immoral, and 63% of Democrats say the same about Republicans. Trust in public institutions has plummeted, with Congress at the bottom of the pile—this, at the very time that problem-solving is needed on a wide range of issues including immigration, abortion, the economy and multiplying wars overseas.

The natural response to duress of any type is flight or fight. We see this response playing out in our American political moment, including (and arguably especially) among Christians. For Christians tired out by our political moment, the “flight” response is grooved by that old Gnostic thinking that God cares only about eternal souls anyway. Nations, culture, humanity’s suffering or history’s arc are of little relevance to his work; it’s heaven that lasts. Under this belief, Christians may be tempted to isolate themselves in communities of similarly minded people and ride out an increasingly secularized and disoriented culture from a distance. Political scientists talk about this group as the “Exhausted Majority,” tuning out from politics all together. Among Christians, we might say it is Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option, a strategic separation of believers from public life.

For others, the “fight” response might be more alluring. The temptation to grab political powers and usher in a Christian nation has titillated since Constantine. Certainly today, many Christians are biting at the bit for political dominance and revenge for the secular progressive enemies who discredit and discriminate against Judeo-Christian values and beliefs. There’s a belief that our country would be better off with Christianity consecrated in the halls of political power and for Christianity to once again become the dominant religion (as opposed to the swelling ranks of religious nones) via political action. Among evangelical Christians, this group is concentrated in MAGA, as documented in Tim Alberta’s The Kingdom, The Power, and The Glory.

Far from new political responses, these are the oldest there are. They are right there on display in the Bible. Ancient Jewish belief was awash in the expectation—from the Torah to the manger—that the coming Messiah would overthrow the system of government and usher in a new kingdom. Instead, Christ was executed at the hands of the Romans, while not ruling out that he was a political leader (“You say that I am <King of the Jews>,” he says to Pilate). After the execution and scattering of nearly all of Jesus’ disciples and the invasion of Jerusalem and raiding of the temple, the early Church surely would have been tempted to run for the hills. Yet the records of the early Church as preserved by Larry Hurtado and Rodney Stark document a community rooted in pagan cities and loving its neighbors through the power of the Holy Spirit.

From Jesus’ life and the early Church, we see a rejection of the twofold temptation to fight the powers or to flee from them. These responses elevate political power, rather than recognizing that there’s another power to which all others submit. Nor do we see a middle way or political compromise in the Bible. The Christian answer to politics is far more radical. It’s a new creation altogether.

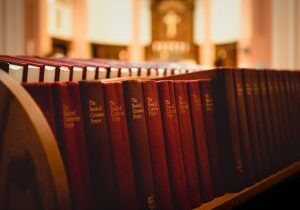

The Christian response to politics is to be the Church through the power of the Holy Spirit: a living, breathing community, set apart by its love of God and pouring out to the world. It is the first fruits of the new Kingdom of God. As beautifully communicated in the first chapter of Ephesians, paraphrased in The Message, “The church, you see, is not peripheral to the world; the world is peripheral to the church. The church is Christ’s body, in which he speaks and acts, by which he fills everything with his presence.” (Ephesians 1:20-23 The Message)

The Church is where there’s an alternative “polis” to the politics of the moment, a community united in its love of God and not self, which pours out to others around it and demonstrates all that a secular culture on its own cannot achieve: true equality, generosity, humility, kindness, justice. The Church is where Scriptural values and prayerful wisdom are sought in ways that cut across the issues of the day and our modern political parties in ways that help to hold politicians of all types to account. (I have yet to see a pro-life, climate loving, poor-championing and immigrant-gentle party emerge in our politics!) The Church is a place of hope because what’s to come is not uncertain. We know how the story ends with the New Heavens and New Earth and that mysteriously, nothing good will be lost between now and then.

The Church, at her best, provides a more compelling counter to politics than any policy position or candidate can because it carries the weight of an entire Kingdom: a Kingdom beyond any specific place, time, moment or political divides. As Henrik Berkhof wrote in his book Christ and the Powers (1977):

By her very presence she breaks through that unshaken stability of life under the Powers, which we know and marvel at in ancient civilizations. She is made up of men who see through the deception of the Powers, refusing to run after isms. Standing within the community of a people or a culture, their presence is an interrogation, the questioning of the legitimacy of the Powers. By her faith and life the church of Christ labels the dominion of the Powers as un-self-evident.

This election cycle is an invitation for Christians in America—or perhaps better thought of as that soft slap in the cheek that an Anglican gets upon church confirmation—to realize the door opened for political engagement for Christians by Christ. It is to be the Church: an outpost of the new Kingdom that is breaking through not in some distant harp-playing future, but in a visible living breathing community of people here and now through the power of the Holy Spirit.

While the aim of the Church (and Christ!) is not politics, out of the overflow of love for God and others, it will inevitably influence it. This is the story of the last 2,000 years. This is the cloud of witnesses American Christians in the local Church are invited to join in faith and action today.

Instead of starting with discouraging politics and going to the Church’s response, as Christians, our political response is first found in being the Church.