The Counter-Cultural Gift of Sabbath

Chris+ Myers

Tim Keller has often remarked that in whatever culture Christianity takes root, the way Christians relate to money, sex and power will always in some sense present a challenge to the culture. I think he is right, but I also think the way we use and approach time and work ought to stand in contrast to our culture, particularly in Western cultures like ours where the logic of capital and productivity so thoroughly and uncritically shapes our imaginations. And I believe that the practice of Sabbath can stand as a counter-witness to distorted uses of time and energy.

Tim Keller has often remarked that in whatever culture Christianity takes root, the way Christians relate to money, sex and power will always in some sense present a challenge to the culture. I think he is right, but I also think the way we use and approach time and work ought to stand in contrast to our culture, particularly in Western cultures like ours where the logic of capital and productivity so thoroughly and uncritically shapes our imaginations. And I believe that the practice of Sabbath can stand as a counter-witness to distorted uses of time and energy.

Sabbath presents a counter-logic by offering a different way of imagining time and our place in the world. In the Old Testament, both the grammar of creation and the grammar of redemption define the Sabbath command. This might seem surprising because when we first think of Sabbath, we probably think of it in terms of the story of creation. And indeed, this is how Moses speaks of it in Exodus 20 when he first gives the Sabbath command as part of the Ten Commandments. In that context, the Sabbath is linked with the fundamental rhythm of the creational week, where the day of rest is a gift of blessing. We are invited through Sabbath to sit back and enjoy the bounty of creation. In this sense, our rest is meant to mirror God’s rest. Just as God pulled back to survey and to enjoy all that he had made and all that he had declared good, so too are we meant to step back and enjoy the world that we have been given by him. This is very easy to forget, and because it is in the context of a command, it might be easy to miss this; but it is not just a holy day, but a blessed day (Exodus 20:11). It is a gift. Jesus, of course, understood this when he said that the Sabbath was made for humanity and not humanity for the Sabbath.

While Exodus 20 provides the creational meaning of Sabbath, Deuteronomy 5 provides the redemptive meaning of Sabbath. In this context Moses tells Israel concerning the Sabbath, “You shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Therefore, the Lord God commanded you to keep the Sabbath day” (Deuteronomy 5:15). Sabbath is once again a gift, but here it is a gift of redemption given to a people who have been delivered from slavery. But it is more than this too. Sabbath is not just a gift of rest for you but for your animals, for your servants, for all your implements of labor. And the implicit warning is to not become like Egyptians, not succumb to the temptation to become unrelenting taskmasters and submit your servants and all your implements of work to unceasing labor.

For us, in the time and place where we live, we need to be reminded of the redemptive meaning of Sabbath and the temptation to be unrelenting taskmasters, both to ourselves and to others. What links the creational and redemptive meaning of Sabbath is the reality of the world as gift. Whatever we have, we have not primarily as the fruit of our labor, but as a gift from God. But if we never stop, if we never rest, we never have the chance to remember this and to be filled with gratitude for the gift given and with humility for the reality that we are not really in charge.

Suggested Resource:

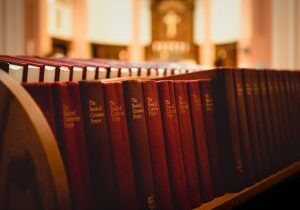

This Day: Collected & New Sabbath Poems by Wendell Berry

The best poetry is about noticing and receiving and so is an act of contemplation, which is itself a posture of reception. What I mean is that when we contemplate the world, we open ourselves up to the possibility of receiving the world as a gift. The fundamental logic of Sabbath is not simply that there is a day of rest, but rather that creation is a gift, and we must receive it such. The world is not simply a domain to be used, but a gift to be received. The posture of Sabbath is receptivity, and Wendell Berry knows that almost better than anybody.

Chris Myers serves as the Associate Rector of St. Bartholomew’s Anglican. He graduated from Redeemer Seminary with an M.Div. in 2013 and was ordained as a priest in the Anglican Mission in May of 2015. He is currently doing doctoral work in theology at Durham University (UK). He and his wife Morgan have two delightful daughters, Eleanor and Rowan.

Category: Discipleship, Spiritual Growth

Tags: rest, Sabbath, spiritual disciplines, Text, time