Three Ways the Book of Common Prayer Shapes Us for Mission

Guest

By Rev. Christopher Caudle

I bought my first copy of the Prayer Book to impress God with better prayers than I had been praying on my own. The prayers were beautiful and their vocabulary matched the version of the Bible I thought God liked best. There were even charts in the front and back of the book to keep these polished intercessions launching on an ambitious schedule. I was in college and struggling to pray. The used bookstore seemed as good a retreat center as any, and it was there that I first discovered the Book of Common Prayer.

I bought my first copy of the Prayer Book to impress God with better prayers than I had been praying on my own. The prayers were beautiful and their vocabulary matched the version of the Bible I thought God liked best. There were even charts in the front and back of the book to keep these polished intercessions launching on an ambitious schedule. I was in college and struggling to pray. The used bookstore seemed as good a retreat center as any, and it was there that I first discovered the Book of Common Prayer.

It was a huge gamble, because I was from the branches of the church tree that cultivated confident, extemporaneous prayers enthused by the Spirit in the moment of petition or praise. But, the book was on sale and I was struggling with both enthusiasm and confidence.

It was a huge gamble. Only the passing of time could measure its success. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer set out to create a book of prayers for all the Christians in his realm. The rubrics would find everyone, from Archbishop to apprentices “all devoutely kneelyng…” His vision for the book was framed and fueled by his mission.

The mission of a church restored to scriptural truth and the proven wisdom of the Christian past. A church calling all the souls of the nation to respond to the Gospel; be strengthened by the God’ gracious sacraments; and be formed to follow Christ as a unified body. A book of liturgy and piety to both instruct and inspire.

Other churches in those times of tumultuous change pursued similar goals with councils and catechisms, but Cranmer and our tradition bet that the surest path to durable formation and lasting restoration of a holy, healthy church was through teaching people how to pray. Other pastoral duties and virtues would find their place within the context of a worshipping and praying community. Change how a person encounters God and everything will change.

Long praised for its beautiful language, evocative biblical imagery, and Christo-centricity, the book is more than the sum of its eloquence or craft. It is a distilled summary of Christian faith and practice, a conserving center to a tradition both wide and turbulent since its inception. As Anglicans, we are familiar with the Prayer Book given its pedigree and regular use in our communities. As members of The Anglican Mission, the Book of Common Prayer can shape us in three strategic ways especially suited for our current mission.

1. The Prayer Book reminds me that new situations require new ways of speaking if I want the good news to remain clear.

Ironic, isn’t it, that the fruit of Cranmer’s bold choice to frame the liturgy in a language understood by the people is now sometimes seen to be an impediment to mission? While the words of the Prayer Book have seen updates from edition to edition, the Prayer Book’s strategy is often overlooked.

The 1662 edition included two new services that serve as favorite challenges to stay attentive to the opportunities of new situations. Forms of Prayer to be Used at Sea was added to respond to the growing maritime role of the English nation. Of course, storms and pirates drew prayer from sailors’ lips before this liturgy was printed. But the church, caring that their members were now praying and exercising faith on water rather than on land, equipped them to pray scripturally, evangelistically and in unity with those on board as well as with those in port. This commitment to apply the truth of God’s protection, power and grace specifically to situations that earlier generations of Christians rarely faced challenges me to notice and respond similarly. Not just as an individual, but as a member of a church that is on mission.

Similarly, The Ministration of Publick Baptism to Such as are of Riper Years addressed growing numbers of people who had not been baptized as children due to religious strife and poor instruction. Rather than simply stand back and lament the darkness of their day or reject those who had not been reared in the church, the church reexamined evangelism in its day and instituted this rite for the baptism of adults, anticipating continued conversions both in England and among the new peoples their citizens encountered. This initial turn towards recovering the missionary expansion of the church would explode in following centuries through the work of mission societies, frontier works and church plants. Similar opportunities exist in our day, and this missional model continues to serve us.

These changes, however, are not at the whim of any individual, but done through authority, by the common mind and prayer of the church, so that inquirers know that their welcome goes beyond the personal temperament of the local parish but is the settled commitment of the church.`

2. The Prayer Book reminds me that I am part of a community.

It was intimidating to open my new (used) Prayer Book and navigate its services and prayers. Similar stories abound. What I missed was the book’s own assumption of a community at prayer. Learning to use this book is designed to occur with others. What was mystifying when working alone quickly began to feel manageable and eventually automatic with the hints and nudges of fellow pray-ers. All prayer is corporate, even when we pray alone, for we are all members of the one body of Christ. We use the Prayer Book, not for occasional doses of nostalgia, but to join our single voice with the unified voice of our sisters and brothers, whether assembled here in our small group or commuting by train across the city. Learning to see the collects or Compline as power tools rather than museum pieces can help us focus and exercise our intercession as a parish family. The rites and rubrics everywhere assume that we will be with one another when we pray, and even when we aren’t, we are drawn to remember and make requests for this community of which we are a member.

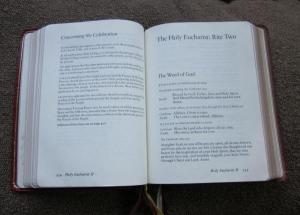

Whether we are hearing and tasting the gospel in the Holy Communion, witnessing the rebirth of a new believer at the font, or commending the soul of a friend to joy and felicity after they are delivered from the burden of the flesh, the book makes one point very well. Only the good news of Jesus Christ can hold us together in life and death and as a body bearing His name. The book’s common language for unique moments binds us both in rejoicing and sorrow. Every new instance of confirmation, marriage, anointing, reconciliation and new ministry reminds us of God’s promises from scripture and past faithfulness in our own common life.

3. The Prayer Book reminds me that my own formation in the way of Jesus is a lifelong work of grace.

Observers of this book in practice sometimes wonder either about its numerous details or about its limited range of services, but for many Christians around the world experience has taught that the two together reveal its strength. The Prayer Book synchronizes the gospel of Jesus Christ and our discipleship to the many chapters of life in this world. In a series of concentric, expanding circles, we trace the good news of Christ expanding to encompass all of life.

Eight years ago, Bishop Greene ordained me after hearing my vow to “be loyal to the doctrine, discipline, and worship of Christ as this Church has received them.” At the time, I was still trying to remember exactly how to set the Lord’s Table or when to exclude Alleluia from the dismissal. While this vow certainly clarified the order of service for Sundays, over time it has done far more. It also offers specific patterns of formation for the minister who will represent Christ in ministry. At the end of the day, ministry in the name of Jesus is also ministry in the name of His body, the church, and this church places its ambassadors under vows to be formed personally by the pattern of teaching and life that we commend to others. The Great Commission is vectored for me in the wisdom of starting with prayer.

Helping others sharpen their own portrait of God by the traits enumerated in the Prayer Book forms a systematic theology warmed by the mercy of God in Jesus and weighted to the proclamation of saving grace. The practice of common prayer expands into a lifelong plan of discipleship, distilling in me (I pray) the scriptural riches summarized in the patrimony of our Anglican pioneers.

Making a turn to use the Prayer Book as it was first given focuses my perspective towards discerning new opportunities for mission. Its powerful language accompanies strategic principles, and remains a powerful tool for vernacular ministry contextualized for the community in confidence that the good news of Jesus has meaning for every stage and station of life. I would enjoy hearing your experiences as well.

Christopher Caudle is the Assistant Rector at New Covenant Anglican Church in Winter Springs, Florida. He and his wife Marci have three amazing children: Atticus, Emeline and Samuel.